By Brad Dieter MS CISSN CSCS.

Whey protein (WP) supplementation has recently gained popularity amongst athletes as it is reported to improve athletic performance. WP is a popular dietary protein supplement purported to provide improved muscle strength and body composition due to greater a compliment of essential amino acids and branched chain amino acids and to result in greater biological value (1-4). Additionally, WP supplementation has shown to reduce oxidative stress through increasing endogenous glutathione production and improve compromised gut health associated with intense exercise (5-8). While the a majority of the research and topics covered in this post are WP supplementation specific, I want to remind everyone that whole foods sources of whey protein may be superior in terms of nutrient synergy than WP supplementation; however, the research surrounding that issue is not well established.

Increase Strength and LBM – Most athletic events are reliant upon force production of muscles, with greater ability to produce force associated with improved performance. As force is equal to mass x acceleration (F=M*A), increasing the muscle mass is the most common way athletes aim to increase force production. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy requires proper resistance training and nutritional status in which muscle protein synthesis (MPS) exceeds muscle protein breakdown (MPB). One of the major concepts in the literature surrounding skeletal muscle hypertrophy is the idea of net protein balance (NPB). NPB is defined as MPS minus MPB (NPB = MPS – MPB). Thus, if MPS is greater than MBP, skeletal muscle hypertrophy will occur (9). One of the critical factors influencing MPS and MBP is the availability of amino acids (10, 11). WP supplementation is a source of high biological value amino acids and has been purported to increase muscle mass and strength.

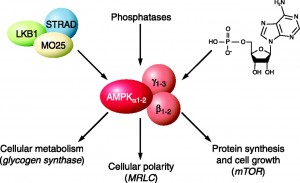

There is an extensive body of research surrounding the efficacy of WP supplementation in increasing strength and muscle mass. The results of the research are not entirely unequivocal; however, a significant amount of evidence suggests that WP increases both strength and muscle mass (12-15). Additionally, researchers have recently shown that the constituents of whey protein upregulate the cell signaling pathways responsible for muscle protein synthesis and muscle hypertrophy, specifically the mTOR pathway (16).

Whey Protein and Glutathione – Oxidative stress refers to an imbalance between antioxidant defense systems and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (17). Oxygen consumption during heavy exercise can increase up to 100 times normal resting levels, thus increasing the production of free radicals and resulting in oxidative stress. Although the data are not unequivocal, evidence exists showing increased free radical production and cellular damage following heavy exercise (18). Athletes are at a higher risk of elevated oxidative stress due to the increased pro-oxidative process they expose themselves to than their non-athletes counterparts (19). The increased levels of ROS produced during heavy exercise must removed by the body’s endogenous antioxidant system in order to maintain oxidative balance

Glutathione, the most abundant and important antioxidant, is a tripeptide synthesized from the amino acids L-cysteine, L-glutamic acid, and glycine (20). It is the most important redox couple and plays crucial roles in antioxidant defense, nutrient metabolism, and the regulation of pathways essential for whole body homeostasis (21). Additionally, glutathione serves as a regulatory compound in the activation of the circulation agents of the immune system, lymphocytes (22). It is apparent that glutathione is a critical compound in maintaining health and glutathione deficiency has been linked to numerous pathological conditions including, cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, cystic fibrosis, HIV and aging (23). Glutathione is of particular interest in the athletic population as the concentration of glutathione varies considerably as a result of nutritional limitation, exercise, and oxidative stress.

The intense physical demands of athletics places athletes’ bodies under high levels of physiological stress. Glutathione plays a critical role in maintaining normal redox status during exercise (24, 25). Furthermore, exhaustive exercise has been shown to reduce glutathione status (24, 25, 26), thus indicating the need for bolstered levels of glutathione in athletes. Researchers have shown that the amino acid cysteine is the rate-limiting factor in glutathione synthesis (27, 28). Therefore, the inclusion of cysteine rich protein sources may prove efficacious in increasing glutathione synthesis rates by providing ample amounts of cysteine to the amino acid pool. Supplementation with free cysteine is not advised however as it spontaneously oxidized and has shown to be toxic (29). Dietary sources of cysteine present as cystine (two cysteines linked by a disulfide bond) are more stable than free cysteine and properly digested. WP supplements, including WP isolate and WP concentrate are protein sources rich in cysteine and deliver cysteine to the cells via normal metabolic pathways (30,31). By providing abundant cysteine, WP supplementation allows cells to replenish and synthesize glutathione without adverse effects (31) (Figure 1.). Thus, WP supplementation may serve to bolster the endogenous production of glutathione and improve oxidative stress in athletes.

The use of WP supplementation to mitigate a training-induced decline in blood glutathione levels has been studied extensively. Researchers have shown that WP supplement is beneficial in maintaining normal physiological levels of glutathione in athletic and non-athletic populations in response to exercise (32-34). Furthermore, researchers have shown that WP improves the athlete’s ability to deal with acute oxidative stress and WP may serve as a safe and effective alternative source of antioxidants for prevention of athletic injuries and sickness caused by excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) (35). The research regarding WP supplements and glutathione status supports the use of WP in athletics to improve health status in athletes by augmenting the endogenous antioxidant system.

Whey Protein and Immune Function – Strenuous exercise and heavy training regimens are associated with depressed immune cell function (36-40). Furthermore, inadequate or inappropriate nutrition can compound the negative influence of heavy exertion on immunocompetence. Suppression of the immune predisposes the individual to an increased risk of infection.

Athletes increase both the volume and intensity of their training a certain stages of the season that may result in a state of overreaching or overtraining. Recent evidence has emerged indicating that immune function is indeed sensitive to increases in training volume and intensity. Although the research has not shown that athletes are clinically immunocompromised during these periods of depressed immune function, it may be sufficient to increase the risk of contracting common infections.

As the components of the immune system are highly dependent on amino acids, endogenous and dietary amino acids can impact the state of the immune system. In comparison to other protein sources, research shows that whey proteins are unique in their ability to promote strong immunity through several beneficial compounds including: glutamine, α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin, and minor fractions such as serum proteins, lactoferrin, as well as a series of immunoglobulins (41-43).

Whey Protein and Gut Health – Intense physical exercise leads to reduced splanchic blood flow, hypoperfusion of the gut, and increased intestinal temperatures (44). Reduced intestinal blood flow and high intestinal temperatures during intense exercise can lead to intestinal barrier dysfunction through increased permeability of the tight junctions (5, 8). The increased permeability of the intestinal wall leads to invasion of Gram-negative intestinal bacteria and/or their toxic constituents (endotoxins) into the blood circulation (45-47). Endotoxins are highly toxic lipopolysaccharides (LPS) of the outer cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria. LPS are a major trigger in vivo for the host immune response via induction of the cytokine network (45). (Jeukendrup, et al., 2000). This process, endotoxemia, can result in increased susceptibility to infectious- and autoimmune diseases, due to absorption of pathogens/toxins into tissue and blood stream (48).

The field of intestinal permeability is relatively and long-term prospective studies have yet to clearly identify the potential hazards of chronic, low-grade levels of intestinal permeability. However, recent research has established a link between intestinal permeability and a host of autoimmune diseases including Chron’s disease, Hashimoto’s Thyroditis, lupus erythmatosis, psoriasis, and rheumatoid arthritis (49-53). Additionally, intestinal permeability has been associated with mental illness including schizophrenia and depression (54,55).

As previously mentioned, tight junctions constitute the major component of gut barrier function and acts as physical and functional barrier against the paracellular penetration of macromolecules from the lumen (56,57). Therefore, the regulation of tight junction permeability is critical in maintaining gut integrity and reducing the exposure of the body to endotoxins. The amino acid glutamine is critical in maintaining the integrity of these tight junctions (56). Glutamine, the most abundant amino acid in the blood, is considered a “conditionally essential” amino acid (Figure 2.) (56). Under normal conditions glutamine is produced in sufficient quantities in the body to maintain the normal physiological functions. However, under stressful situations, such as exercise, endogenous production of glutamine insufficient and the body must rely on exogenous sources of glutamine to meet its requirements.

Glutamine supplementation has been shown to improve gut permeability through restoration of tight junction integrity caused by a variety of physiological stressors through multiple molecular mechanisms (58-60). Additionally, glutamine supplementation has proven effective in reducing exercise induced intestinal permeability (61). WP is a rich source of glutamine and researchers have shown that WP supplementation is capable of reducing intestinal permeability (62,63). Therefore, WP may be beneficial in reducing exercise induced intestinal permeability and the risk of endotoxemia and autoimmune disorders.

Summary

Whey protein is an excellent source of a wide range of amino acids and additional nutrients that are beneficial to health. Whey protein has been shown to increase lean body mass in conjunction with resistance training, bolster glutathione status, have immunomodulatory effects and improve gut health. A healthy, well balanced diet may be enhanced with whey protein through either whole food sources or occasional whey protein supplements.

Bibliography

1) Burke, D. G., Chilibeck, P., Davison, K., & Candow, D. (2001). The effect of whey protein supplementation with and without creatine monohydrate combine with resistance training on lean tissue mass and muscle strength. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism , 11, 349-364.

2) Coburn, J. W., Housh, D., Malek, M., Beck, T., Cramer, J., Johnson, G., et al. (2006). Effects of leucine and whey protein supplementation during eight weeks of unilateral resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research , 20 (2), 284-291.

3) Frestedt, J. L., Zenk, J., Kuskowski, M., Ward, L., & Bastian, E. (2008). A whey-protein supplement increases fat loss and spares lean muscle in obese subjects: A randomized human clinical study . Nutrition & Metabolism , 5 (8), 1-7.

4) Willoughby, D. S., Stout, J., & Wilborn, C. (2007). Effects of resistance training and protein plus amino acid supplementation on muscle anabolism, mass, and strength. Amino Acids , 32 (4), 467-477.

5) Lambert, G. P. (2009). Stress-induced gastrointestinal barrier dysfunction and its inflammatory effects. Journal of Animal Science , 87 (E. Supplement), E101-E108.

6) Low, P. L., Rutherfurd, K., Gill, H., & Cross, M. (2003). Effect of dietary whey protein concentrate on primary and secondary antibody responses in immunized BALB/c mice . International Immunopharmacology , 3 (3), 393-401.

7) Micke, P., Beeh, K., Schlaak, J., & Buhl, R. (2001). Oral supplementation with whey proteins increases plasma glutathione levels of HIV-infected patients. European Journal of Clinical Investigation , 31 (2), 171-178.

8) Pals, K. L., Chang, R., Ryan, A., & Gisolfi, C. (1997). Effect of running intensity on intesttinal permeability. Journal of Applied Physiology , 82, 571-576.

9) Hulmi, J. J., Lockwood, C., & Stout, J. (2010). Effect of protein/essential amino acids and resistance training on skeletal muscle hypertrophy: A case for whey protein . Nutrition & Metabolism , 7 (51).

10) Dickinson, J. M., & Rasmussen, B. (2011). Essential amino acid sensing, signaling, and transport in the regulation of human muscle protein metabolism. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care , 14 (1), 83-88.

11) Li, J. B., & Jefferson, L. (1978). Influence of amino acid availability on protein turnover in perfused skeletal muscle . Biochimica et Biophysica Acta , 544 (2), 351-359.

12) Esmarck, B., Andersen, J., Olsen, S., Richter, E., Mizuno, M., & Kjaer, M. (2001). 18. Timing of postexercise protein intake is important for muscle hypertrophy with resistance training in elderly humans. Journal of Physiology , 535, 301-311.

13) Cribb, P. J., Williams, A., Carey, M., & Hayes, A. (2006). The effect of whey isolate and resistance training on strength, body composition, and plasma glutamine. International Journal of Sports Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism , 16 (5), 494-509.

14) Buckley, J. D., Thomson, R., Coates, A., Howe, P., DeNichilo, M., & Rowney, M. (2010). Supplementation with a whey protein hydrolysate enhances recovery of muscle force-generating capacity following eccentric exercise . Journal of Science in Medicine and Sport , 13, 178-181.

15) Tipton, K. D., Elliot, T., Cree, M., Wolf, S., Sanford, A., & Wolf, R. (2004). Ingestions of casein and whey proteins result in muscle anabolism after resistance exercise. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 36, 2073-2081.

16) Hulmi, J. J., Tannerstedt, J., Selanne, H., Kainulainen, H., Kovanen, V., & Mero, A. (2009). Resistance exercise with whey protein ingestion affects mTOR signaling pathway and myostatin in men. Journal of Applied Physiology , 106, 1720-1729.

17) Sachdev, S., & Davies, K. (2008). Production, detection, and adaptive responses to free radicals during exercise. Free Radical Biology & Medicine , 44 (2), 215-223.

18) Adams, A. K., & Best, T. (2002). The role of antioxidant in exercise and disease prevention. The Physician and Sports Medicine , 30 (5), 2002.

19) Lowery, L. (2001). Antioxidants supplements and exercise. In J. Antonio, & J. Stout (Eds.), Sport Supplements (pp. 260-278). Philidelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins.

20) Thomas, J. A. (1999). Oxidative stress and oxidant defense. In M. Shils, J. Olson, M. Shike, & A. Ross (Eds.), Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease (pp. 751-782). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

21) Wu, G., Fang, Y., Yan, S., Lupton, J., & Turner, N. (2004). Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health. Journal of Nutrition , 134, 489-492.

22) Droge, W. (1996). Modulation of the immune response by cysteine and cysteine derivatives. Italian Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition , 14, 1-4.

23) Townsend, D. M., Tew, K., & Tapiero, H. (2003). The importance of glutathione in human disease. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy , 57, 145-155.

24) Li, J. J., & Fu, R. (1992). Responses of glutahtione system and antioxidant enzymes to exhaustive exercise and hydroperoxide. Journal of Applied Physiology , 72 (2), 549-554.

25) Kerksick, C., & Willoughby, D. (2005). The antioxidant role of glutathione and n-acetyl-cysteine supplements and exercise-induced oxidative stress. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition , 2 (2), 38-44.

26) Gohil, K., Viguie, C., Stanley, W., Brooks, G., & Packer, L. (1988). Blood glutathione oxidation during human exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology , 64 (1), 115-119.

27) Lyons, J., Rauh-Pfeiffer, A., Yu, Y., Lu, X., Zurakowski, D., Tompkins, R., et al. (2000). Glood glutathione synthesis rates in health adults receiving a sulfur amino acid-free diet. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , 97 (10), 5071-5076.

28) Rathbun, W. B., & Murray, D. (1991). Age-related cysteine uptake as rate-limiting in glutathione synthesis and glutathione half-life in the cultured human lens. Experimental Eye Research , 53 (2), 205-212.

29) Meister, A. (1984). New aspects of glutathione biochemisty and transport selective alterations of glutathione metabolism. Nutrition Reviews , 42, 397-410.

30) Chitapanarux, T., Tienboon, P., Pojchamarnwiputh, S., & Leelarungrayub, D. (2009). Open-labeled pilot study of cysteine-rich whey protein isolate supplementation for nonalchoic steatohepatitis patients. Hepatology , 24, 1045-1050.

31) Sindayikengera, S., & Xia, W. (2006). Nutritional evaluation of caseins and whey proteins and their hydrolysates from Protamex. Journal of Zhejian University Science B , 7 (2), 90-98.

32) Mariotti, F., Simbelie, K., Makarious-Lahham, L., Huneau, J., Laplaize, B., Tome, D., et al. (2004). Acute ingestion of dietary proteins improves post-exercise liver glutathione in rats in a dose-dependent relationship with their cysteine content. Journal of Nutrition , 134, 128-131.

33) Middleton, N., Jelen, P., & Bell, G. (2004). Whole blood and mononuclear cell glutathione response to dietary whey protein supplementation and trained male subjects. International Journal of Food Science Nutrition , 55 (2), 131-141.

34) Vatani, D. S., & Golzar, F. (2012). Changes in antioxidant status and cardiovascular risk factors of overweight young men after six weeks supplementation of whey protein isolate and resistance training. Appetite , 59, 673-678.

35) Xu, R., Liu, N., Xu, X., & Kong, B. (2011). Antioxidative effects of whey protein on peroxide-induced cytotoxicity. Journal of Dairy Science , 94 (8), 3739-3746.

36) Gleeson, M. (2007). Immune function in sport and exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology , 103, 693-699.

37) Gleeson, M., McDonald, W., Cripps, A., Pyne, D., Clancy, R., & Fricker, P. (1995). The effect on immunity of long-term intensive training in elite swimmers . Clinical & Experimental Immunology , 102 (1), 210-216.

38) Baj, Z., Kantorski, J., Majewska, E., Zeman, K., Pokoca, L., Fornalczyk, E., et al. (1994). Immunological status of competitive cyclists before and after the training season. International Journal of Sports Medicine , 15 (6), 319-324.

39) Bury, T., Marechal, R., Mahieu, P., & Pirnay, F. (1998). Immunological status of competitive football players during the training season. International Journal of Sports Medicine , 19 (5), 364-368.

40) Shepard, R. J., Rhind, S., & Shek, P. (1994). Exercise and the immune system. Natural killer cells, interleukins and related responses. Sports Medicine , 18 (5), 340-369.

41) Cribb, P. J. (2005). U.S. whey proteins in sports nutrition. U.S. Dairy Export Council.

42) Cribbs, P. J. (2004). Whey proteins and immunity. U.S. Dairy Export Council.

43) Walzem, R. M., Dillard, C., & German, J. (2002). Whey components: millennia of evoluation create functionalities for mammalian nutrition: What we know and what we may be overlooking. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition , 42 (4), 353-375.

44) Qarnar, M. I., & Read, A. (1987). Effects of exercise on mesenteric blood flow in man. Gut , 28, 583-587.

45) Jeukendrup, A. E., Vet-Joop, K., Sturk, A., Stegen, J., Senden, J., Saris, W., et al. (2000). Relationship between gastro-intestinal complaints and endotoxaemia, cytokine release and the acute-phase reaction during and after a long-distance triathlon in highly trained men. Clinical Science , 98, 47-55.

46) Lambert, G. P. (2008). Intestinal barrier dysfunction, endotoxemiz, and gastrointestinal symptons: the ‘canart in the coal mine’ during exercise-heat stress? Medicine and Sport Science , 53, 61-73.

47) Van Deventer, S. J., & Gouma, D. (1994). Bacterial translocation and endotoxin transmigration in intestinal ischaemia and reperfusion. Current Opinions in Anaesthiology , 7, 126-130.

48) Lamprecht, M., Bogner, S., Schippinger, G., Steinbauer, K., Fankhauser, F., Hallstroem, S., et al. (2012). Probiotic supplementation affects markers of intestinal barrier, oxidation, and inflammation in trained men; a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial . Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition , 9 (45), 1-13.

49) Sasso, F. C., Carbonara, O., Torella, R., Mezzogiomo, A., Esposito, V., deMagistris, L., et al. (2004). Ultrastructural changes in enterocytes in subjects with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis . Gut , 53 (12), 1878-1880.

50) Caradonna, L., Amati, L., Magrone, T., Pellegrino, N., Jirillo, E., & Cacavvo, D. (2000). Invited review: Enteric bacteria, lipopolysaccharides and related cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease: biological and clinical significance . Journal of the International Endotoxin Innate Immunity , 6 (3), 205-214 .

51) Apperloo-Renkema, H. Z., Bootsma, H., Mulder, B., Kallenberg, C., & van der Waajj, D. (1994). Host-microflora interaction in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): colonization resistance of the indigenous bacteria of the intestinal tract. . Epidemiiology and Infection , 112 (2), 367-373.

52) Hamilton, I., Fairris, G., Rothwell, J., Cunliffe, W., Dixon, M., & Axon, A. (1985). Small intestinal permeability in dermatological disease. QJM , 56, 559-567.

53) Smith, M. D., Gibson, R., & Brooks, P. (1985). Abnormal bowel permeability in ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of Rheumatology , 12 (2), 299-305.

54) Wood, N. C., Hamilton, I., Axon, A., Khan, S., Quirke, P., Mindham, R., et al. (1987). Abnormal intestinal permeability. An aetiological factor in chronic psychiatric disorders? . The British Journal of Psychiatry , 150, 853-856.

55) Maes, M., Kubera, M., & Leunis, J. (2008). The gut-brain barrier in major depression: Intestinal mucosal dysfunction with an increased translocation of LPS from gram negative enterobacteria (leaky gut) plays a role in the inflammatory pathophysiology of depression. Neuroendocrinology Letters , 29 (1), 117-124.

56) Rao, R. K., & Samak, G. (2012). Role of glutamine in protection of intestinal epithelial tight junctions. Journal of epithelial biology and pharmacology , 5, 47-54.

57) Mitic, L. L., & Anderson, I. (1998). Molecular architecture of tight junctions. Annual Review of Physiology , 60, 121-142.

58) Wilmore, D. W., Smith, R., O’Dwyer, S., Jacobs, D., Ziegler, T., & Wang, X. (1988). The gut: A central organ after surgical stress. Surgery , 104, 917-923.

59) Peng, X., Yan, H., You, Z., Wang, P., & Wang, S. (2004). Effects of enteral supplementation with glutamine granules on intesinal mucosal barrier function in severe burned patients. Burns , 30, 135-139.

60) Kozar, R. A., Schultz, S., Bick, R., Poindexter, B., DeSoignie, R., & Moore, F. (2004). Enteral glutamine not but alanine maintains small bowel barrier function after ischemia/reperfusion injury in rates. Shock , 21, 433-437.

61) Hoffman, J. R., Ratamess, N., Kang, J., Rashti, S., KElly, N., Gonzalez, M., et al. (2010). Examination of the efficacy of acute L-alanyl-L- glutamine ingestion during hydration stress in endurance exercise . Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition , 7 (8).

62) Kotler, B. M., Kerstetter, J., & Insogna, K. (2013). Claudins, dietary milk proteins, and intestinal barrier regulation. Nutrition Reviews , 71 (1), 60-65.

63) Benjamin, J., Makharia, G., Ahuja, V., Rajan, K. D., Kalaivani, M., Gupta, S. D., et al. (2012). Glutamine and whey protein improve intestinal permeability and morphology in patients with Chron’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Digestive Diseases and Sciences , 57 (4), 1000-1012.

By Scarlett Blandon, MS RDN. Unless you were a vegan (or a yogi…or maybe a protein powder junky) the chances of you knowing about brown rice protein are slim to none. Rice protein is a novel source of protein derived from the entire rice grain (including bran layer), and is available as

By Scarlett Blandon, MS RDN. Unless you were a vegan (or a yogi…or maybe a protein powder junky) the chances of you knowing about brown rice protein are slim to none. Rice protein is a novel source of protein derived from the entire rice grain (including bran layer), and is available as  a concentrate or isolate just like other protein powders. It offers several benefits that other protein powders do not, but chances are those merits have been drowned out by: (1) the negative stereotypes surrounding rice protein’s plant-based origin; (2) the popularity and media-hype of whey protein. Sure, rice protein might not have all the looks and attractive qualities that whey does, but it’s those unique differences that make it an outstanding alternate protein source for athletes and sports enthusiasts alike. Here are a few reasons why you might consider brown rice protein:

a concentrate or isolate just like other protein powders. It offers several benefits that other protein powders do not, but chances are those merits have been drowned out by: (1) the negative stereotypes surrounding rice protein’s plant-based origin; (2) the popularity and media-hype of whey protein. Sure, rice protein might not have all the looks and attractive qualities that whey does, but it’s those unique differences that make it an outstanding alternate protein source for athletes and sports enthusiasts alike. Here are a few reasons why you might consider brown rice protein: ).

). million Americans diagnosed with Celiac disease and many more who remain undiagnosed3. What’s worse is that damage to the microvilli from gluten can actually cause a person to develop lactose-intolerance, rendering them doubly restricted from those food groups4.

million Americans diagnosed with Celiac disease and many more who remain undiagnosed3. What’s worse is that damage to the microvilli from gluten can actually cause a person to develop lactose-intolerance, rendering them doubly restricted from those food groups4. On the other hand, brown rice protein is derived from rice, a well-known hypoallergenic food source. As a staple food in many cultures (for thousands of years!), rice is highly unlikely to elicit an allergic reaction (or intolerance) and is not surprisingly recommended as a first food for babies. As such, rice protein is expectedly gentle on the GI tract and may offer greater benefit to those athletes or exercise enthusiasts with food allergies, intolerances or sensitivities.

On the other hand, brown rice protein is derived from rice, a well-known hypoallergenic food source. As a staple food in many cultures (for thousands of years!), rice is highly unlikely to elicit an allergic reaction (or intolerance) and is not surprisingly recommended as a first food for babies. As such, rice protein is expectedly gentle on the GI tract and may offer greater benefit to those athletes or exercise enthusiasts with food allergies, intolerances or sensitivities. hexane-free rice protein among other plant proteins, and for Growing Naturals, a consumer brand specializing in hypoallergenic plant proteins and natural lifestyle products. At Axiom and GN she oversees all research-related ventures and nutrition communications. Having worked closely with renowned researchers in the past, she is dedicated to expanding the literature on rice- and other plant proteins while cultivating the knowledge of consumers and manufacturers alike.

hexane-free rice protein among other plant proteins, and for Growing Naturals, a consumer brand specializing in hypoallergenic plant proteins and natural lifestyle products. At Axiom and GN she oversees all research-related ventures and nutrition communications. Having worked closely with renowned researchers in the past, she is dedicated to expanding the literature on rice- and other plant proteins while cultivating the knowledge of consumers and manufacturers alike.