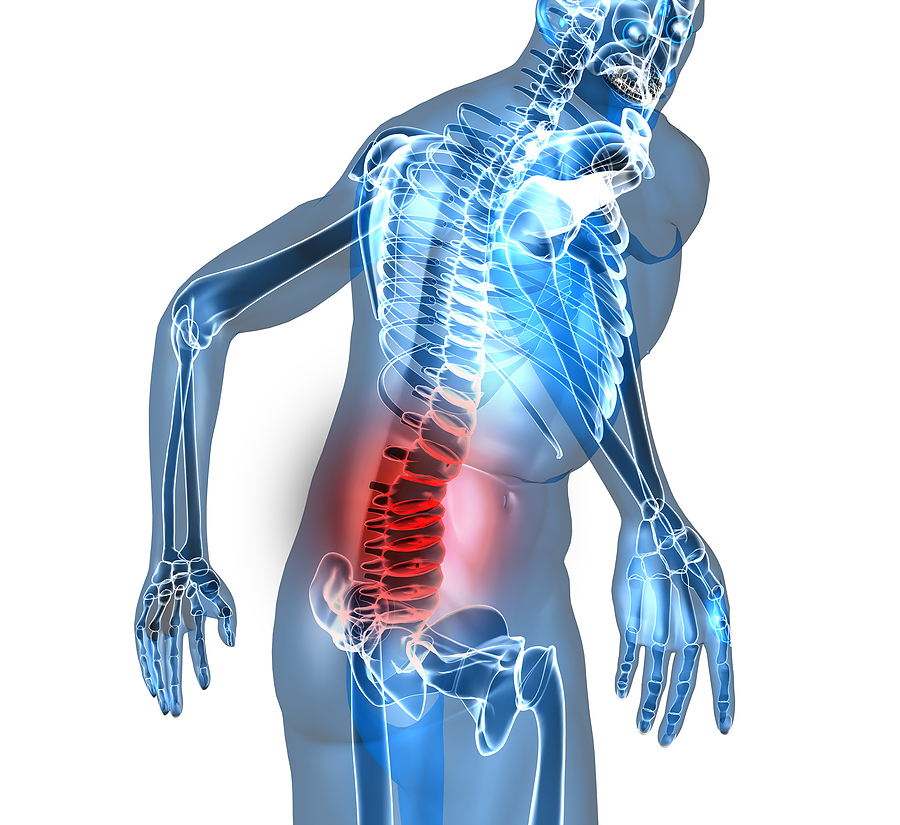

By Aimee Polgar DC-s, CISSN – Approximately 80% of people experience low back pain (LBP) in their life time, and low back pain does not discriminate- men and women are equally affected, with children and adolescents also reporting pain and an increasing number of athletes suffering as well. It is commonly perceived that low back pain only affects the older, overweight, inactive population but the number of collegiate athletes that experience low back pain ranges from 1% to greater than 30% (1, 6, 7)- So what gives?

The majority of acute low back pain is mechanical in nature, meaning that there is a disruption in the way the components of the back (the spine, muscle, intervertebral discs, and nerves) fit together and move (4). Many of these findings however are not visible on conventional radiographs and therefore present a challenge for physicians, physical therapists and athletic trainers when recommending treatment and rehab for athletes with low back pain.

So where do we go from here?

For patients and athletes with no organic cause to their back pain, the initial focus should be on pain management for the acute bout of low back pain and strengthening and rehab for preventative measures. Pain management should focus on decreasing inflammation with an  anti-inflammatory diet, ice and modalities such as interferential current. NSAIDs that are naproxen based (such as Aleve) also have positive outcomes in the acute stage for pain.

anti-inflammatory diet, ice and modalities such as interferential current. NSAIDs that are naproxen based (such as Aleve) also have positive outcomes in the acute stage for pain.

From there it is crucial to keep the athlete moving! Old school methods of management for acute low back pain were bed rest, but it is now known that that is exactly the opposite of what we want to do because intervertebral discs rely on the motion of the spine for nutrition as well as clearance of waste buildup through a process called imbibition. A 2011 study by Dufek et al. showed that backward walking had positive outcomes on pain and general function in athletes with low back pain. The study showed that during backward walking, the typical heel-strike associated with ground contact is eliminated because the toe contacts the ground first. The kinematic difference has the potential to manifest itself in a more anteriorly aligned pelvis which may open up the facet joints in the vertebral column, therefore, help in alleviating the pressure and associated low back pain (3). Results of the study concluded that all LBP subjects reduced self-reported pain and over half significantly increased their low back range of motion. Both groups (pain reporting athletes and non) increased velocity, stride parameters, and low back ROM following 3 weeks of backward walking exercise. It appears that the presence of LBP did not interfere with the ability of participants to adapt to the actions of backward walking. Both groups achieved greater walking velocity with a greater percent increase in stride length versus stride rate.

Adding specific spinal stabilizing exercises is crucial to increase strength in the supportive muscles that we often overlook when training larger muscle groups because support and stability to the low back arises from muscles. Interestingly, it is not strength but coordination between agonist and synergist muscles which plays a pivotal role in resisting injury. Sparto et al., report that spinal loading forces increased during a fatiguing isometric trunk extension effort without a loss of torque output (5). Torque output remained constant because as the erector spinae fatigued, substitution by secondary extensors such as the internal oblique and latissimus dorsi muscles occurred.

Agonist-antagonist muscle coactivation is an important mechanism in preventing spine injury, as well. Cholewicki et al., examined the theory that antagonistic trunk muscle coactivation is necessary to provide mechanical stability to the lumbar spine around a neutral posture (2). The authors found that antagonistic muscle coactivation increased in response to increased axial load on the spine.

Nutritionally it is important to prevent excessive weight gain (which usually is not an issue for athletes but may be for the average individual) as well as maintain a diet sufficient in protein, calcium, phosphorus and vitamin D to maintain healthy bone growth and repair. Hydration status is also largely important to help maintain proper intervertebral disc height, as discs are made approximately of 80% water! And yes, it is true that you may lose up to ¼ – ½” in height by the end of the day due to dehydrated discs!

So what is the take away message here?

Don’t be surprised if athletes and even children report low back pain- it is become more and more common due to the increased stress we put on our spines, but in a healthy individual, it is easily managed and does not need to become a chronic issue. Rule number one, cut back on activity but DO NOT tell your athlete to stop moving. Rule two: manage pain and inflammation primarily and then stabilize the spine with agonist (spinal erectors) and antagonists (abdominals) exercises. And finally, the golden rule: whatever you do all day, stretch the opposite way (and try walking backwards)!!!

References

- Bono CM. Low-back pain in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Amer 2004;86:382-396.

- Cholewicki J, Panjabi MM, Khachatryan A. Stabilizing function of the trunk flexor-extensor muscles around a neutral spine posture. Spine 1997;19:2207-2212.

- Janet Dufek, et al. “Backward Walking: A Possible Active Exercise for Low Back Pain Reduction and Enhanced Function in Athletes.” Journal of Exercise Physiology 2011; Vol14:2

- “Low Back Pain Fact Sheet,” NINDS. Publication date December 2014. NIH Publication No. 15-5161

- Sparto PJ, Paarnianpour M, Massa WS, Granata KP, Reinsel TE, Simon S. Neuromuscular trunk performance and spinal loading during a fatiguing isometric trunk extension with varying torque requirements. Spine 1997;10:145-156.

- Spencer CW, Jackson DW. Back injuries in the athlete. Clin Sports Med 1983;2:191-215.

- Watkins RG, Dillin WH. Lumbar spine injury in the athlete. Clin Sports Med 1990;9:419-448.